Analogy Of The 112th Dipsea Race

The uniqueness of the Dipsea – the oldest trail race in the country – is that it awards its participants head starts based on their age and gender.

In theory, the Dipsea is designed to put the fastest runners at the end of the pack and give others a much fairer opportunity to win the race.

In reality, at the finish line, the Dipsea is like all other foot races. You try to run your fastest.

“The handicaps are set up, but, at the end, it’s personal,” says Bill Rus, the person in charge of researching and adjusting the handicaps each year in The Annual Dipsea.

This past Dipsea race, the 112th Dipsea on June 11, is an example of how the handicap system works. Of the Top 10 finishers, five were male and five were female. Of the Top 10 finishers, eight came from different starting groups. Of the Top 10, there were runners in their teens, their 20s, their 30s, their 50s, and their 60s.

“The Dipsea is handicapped to win, and to be fair among the elite runners by age and gender. It is based on the best of the best in each age and gender group over time, balanced to give equal chances to truly exceptional trail runners,” Rus says. “The composition of the Top 10 has nothing to do with how many people of each gender have entered the race. It only depends on the performance of elite runners by age and gender. A runner must be extraordinary, fit, and ready to make the Top 10. Look at the composition of the Top 10, and I am sure you will agree that the runners on Sunday fit that bill. Performance relative to the best performances by extraordinary runners, based on their actual run times, by age and gender, is what matters.”

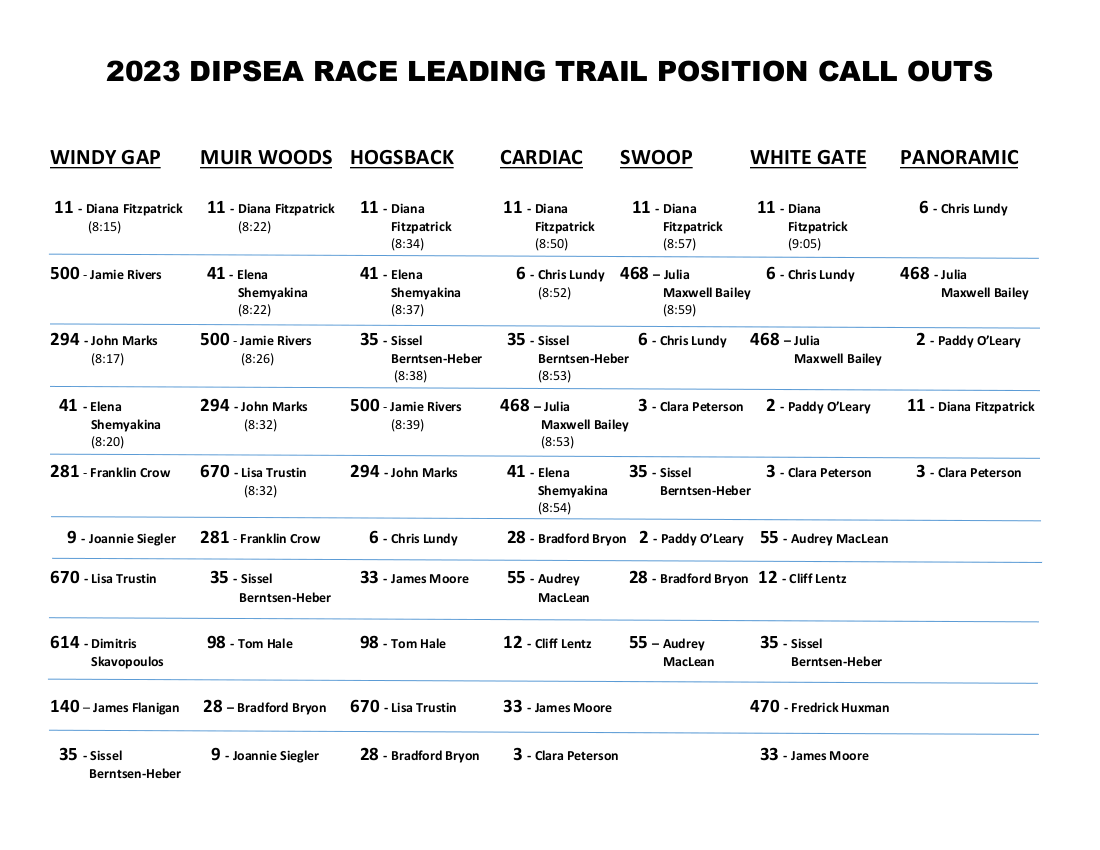

Using the chart above -- furnished by Rob Rowlands of the Marin Amateur Radio Society (MARS) -- the 112th Dipsea can be broken down in a way to show how 65-year-old Diana Fitzpatrick, an elite runner, was able to build a big lead on the 7.5-mile course with 24 head start minutes, then hold off Paddy O’Leary, who had only two head start minutes and hence started the race in Mill Valley 22 minutes behind Fitzpatrick. In other words, Fitzpatrick was already in Muir Woods by the time O’Leary left the starting line in downtown Mill Valley. He still managed to catch and pass Fitzpatrick – and 27-year-old Julia Maxwell Bailey and 52-year-old Chris Lundy -- inside the final mile, yet he was going so fast that he literally traveled faster than the news was relayed to finish Dipsea finish line announcer Barry Spitz, who was anticipating and announcing an all-women battle in the final stretch.

Rowlands’s crew of 27 individual HAM operators were positioned at various spots along the race route for the express purpose of safety. It is their priority to watch runners in case they fall or are injured, which they then report via race bib number to emergency personnel through the Incident Command center located in the parking lot near the finish line in Stinson Beach Park. Secondary to that responsibility is the reporting of the race bibs numbers of the first half dozen or so runners who pass them on the route. These are called “trail position call outs.”

The first HAM operators’ radio call out/report in the 112th Dipsea came from Windy Gap, about a mile into the race. Two-time Dipsea champion Fitzpatrick was in the lead followed by 72-year-old Jamie Rivers, also a two-time Dipsea winner who had the maximum 25-minute head start, and 75-year-old John Marks of Novato, who was third. At Windy Gap, Marks was in position to be on the podium. He wound up in 197th place, but had the thrill of feeling like a leader as did Franklin Crow of Portola Valley who was in fifth place at Windy Gap (he finished 354th) and 78-year-old Dimitris Skavopoulos of Mill Valley who was in eighth place. He finished 469th.

The balance of the handicap system is best exemplified by the initial HAM report from Cardiac, which is the highest point on the course at 1,360 feet above sea level and roughly two-thirds into the race. At that point, the ages of the Top 10 runners in the lead were 65, 52, 59, 27, 64, 65, 17, 58, 68, and 39.

There were call outs provided at seven places on the trail all told. Those updates were radioed to the finish line and relayed to Spitz, who might be the best play-by-play, step-by-step announcer in all of running. He could make grass mowing sound exciting. Though Spitz was expecting to eventually hear Paddy O’Leary’s name in the call outs, his name did not appear on the race update list until O’Leary was in sixth place at the Swoop, about two miles from the finish line. He was still chasing Fitzpatrick, who remarkably needed only eight minutes to get from the top of the Swoop down to White Gate.

“I couldn’t slip, fall, and tumble that fast,” quipped Dipsea Race Director Chris Knez.

By White Gate, O’Leary had risen to fourth place and by Panoramic Highway he was in third place. He had caught and passed Fitzpatrick and two seconds later caught and passed Lundy. But he was going at such a fast clip that by the time O’Leary emerged alone on the final stretch headed to the finish line, the report that he had passed Fitzpatrick at Panoramic had yet to arrive. Spitz knew instinctively that O’Leary was coming fast, but, based on the pace of updates coming into the finish line, the longtime Dipsea race announcer figured he would see any combination of Maxwell Bailey, Lundy, or Fitzpatrick before he would lay eyes on O’Leary. Spitz was amazed as O’Leary, Maxwell Bailey, and Fitzpatrick all set Dipsea records for their age group.

O’Leary became the first runner in their 30s to win the Dipsea since 39-year-old Christie Patterson in 1987. Last year, Eddie Owens, who was injured and did not compete in the 112th Dipsea, was the first runner in his 20s to win the Dipsea since Carl Jensen in 1966. Prior to Owens’s win at age 28, the average age of a Dipsea champion from 1995 to 2021 (excluding 8-year-old Riley Johnson's stunning Dipsea win in 2010) was 60 years old. They all won fair and square according to the handicap system in place.

However, to further ensure that the race offers a fair chance and level running field, so to speak, the Dipsea Race Committee years ago established “champion minutes” which docks one head start minute for three consecutive years for each of its champions. For example, had Owens competed this year he would have moved back with the “scratch” runners. Had he not won the 112th Dipsea, O’Leary would have remained in Starting Group Y for males aged 17 and 33-41, but he will “lose” a head start minute for next year’s race and start in Group Z for males 18-19 and 26-32, if the handicaps remain the same for the 113th Dipsea on June 9, 2024.

But, as Rus, notes, it’s more than “losing” a minute. By moving back one starting group in Mill Valley, O’Leary will have another group of runners ahead of him, thus he inherits in Rus’s words, a “passing tax.” O’Leary will have to pass more runners and that takes additional time.

In the end, the Dipsea did what it was designed to do – give everyone but the scratch runners in a generational race a head start with the mission of continuing a tradition unlike any other in running where the first-place finisher conceivably could be older than the last-place finisher. This year, of the Top 36 runners, five were in their teens and five were in their 60s. Grandparents competing against grandchildren and everyone in between for the grand prize of the Dipsea – a Dipsea Black Shirt if not a championship trophy. To do that, they need a head start and sometimes they do not get the one they want.

Dipsea Hall of Famer Jim “The Birdman” Weil, who conceived the handicapped system for the Dipsea, heard numerous complaints about handicaps over the years. He always had a simple two-word response to critics that still rings true today.

Run faster.