The History of the Women's Dipsea Hike

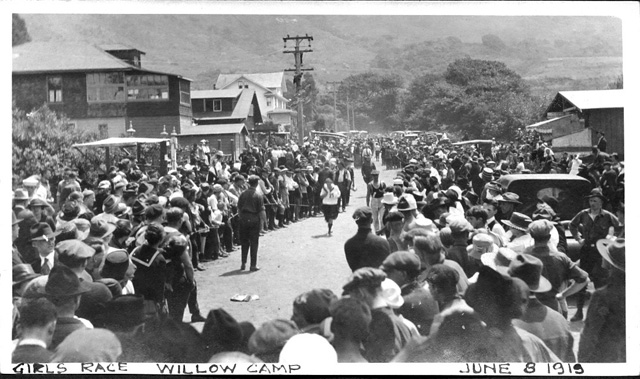

The finish line of the 1919 Women's Dipsea Hike in Willow Camp (now Stinson Beach)

The brainchild of the Women’s Dipsea Hike in 1918 was a man dubbed “The Sultan of the Dipsea.”

George James was an Olympic Club member in San Francisco and an advocate for women’s sports. He organized the Golden Gate Swim for women and then decided to create a cross country race for women over the Dipsea trail covering seven miles from the railroad station in Mill Valley to Willow Camp at Stinson Beach. Edith Hickman, the winner of the inaugural Women’s Dipsea Hike at age 19, was a star in both events.

“When I first originated the Golden Gate Swim for women I was told that it was impossible, as a woman could not stand the exertion,” George wrote in April 1918 issue of the Olympian, the Olympic Club’s monthly magazine since 1912. “When I suggested the Cross County Hike I met with considerable opposition – but from my own observation, I believe that a woman, equally trained, and in the same physical condition as a man, is more game, more tenacious, and has greater endurance.”

According to an Olympic Club scrapbook of newspaper accounts and photos that James kept until his death in 1922, he, as race director, set the rules for the women’s race which was deemed a “hike” to avoid an AAU ban. There were no pacemakers and no professional hikers allowed. The competitors, who had to be 17 or older in age and from the state of California, were advised to take either the 7:45 a.m. or 8:15 ferry to Sausalito because the Golden Gate Bridge was not built until 1937. Their only expense for the Dipsea Women’s Hike was having to pay the round trip train fare from Sausalito to Mill Valley. They had to pick up their racing bibs at the Outdoor Art Club in Mill Valley before the 10 a.m. start. They were given a three-hour time limit to compete the course.

James was given the honor of kissing the first girl to cross the finish line. Miss Hickman also received a silver cup as the winner as the first girl from San Francisco to complete the race.

The Women’s Hike registration for this event has completed. No more applications will be accepted

The first Women’s Dipsea Hike – held on April 21, 1918 -- attracted 148 entries, 134 of whom finished the race, according to a newspaper account. James said 171 started and 148 finished in the Olympian.

To accommodate all the women competitors, the mayor of Mill Valley opened the town hall “for dressing purposes.”

Newspaper photos from the inaugural race reveal that the vast majority of the competitors were wearing hats or caps with long blouses and long skirts and laced up high-top shoes or boots, some with heels.

Each finisher received a commemorative silver bar from the Call Post newspaper, which sponsored the race through 1920. The Call Post also awarded a silver trophy to the champion.

“To me it was a sight to remember, seeing these young ladies in the flower of their youth, with clear eyes, cheeks flushed a picture of health, coming down the stretch, some strong while others began to wobble but all game to the core,” James wrote.

“The winner Miss Edith Hickman is a trained athlete – from the start she was never headed and when she reached Lone Tree she was six minutes ahead of her nearest competitor and from there on she took things easy, finishing the course in one hour and eighteen minutes … Both modest and unassuming Miss Hickman’s victory was a very popular one, particularly with her sister members of the Center Club.”

From there, the Women’s Dipsea Hike took off in popularity. The Call Post called it “one of the most novel and unique competitive athletic contests ever staged in which girls are the only contestants.” It is believed to be the first of its kind sporting event organized exclusively for women in the country.

George appointed Mrs. Claire Shortall to be the athletic director of the first race and recruited Olympic Club businessmen and professionals from San Francisco – most were from the Club’s Dipsea Indians -- to serve roles as race referees, judges, inspectors, times, and scorers at the start, at Lone Tree, and at the finish line. Finishers were handed a luncheon ticket and an automobile ticket to receive a ride back to Mill Valley.

There were refreshments and live entertainment by the Olympic Club Orchestra was provided. The Dipsea Indians hosted an awards dinner – a “big powwow at the clubhouse at Willow Camp” -- in the evening. Mrs. Shortall served as the “official chaperone” for the girls. The Women’s Dipsea Hike became both an athletic and social event.

“One cannot help but admire the splendid spirit manifested by the hikers,” Mrs. Shortall told Frank P. Noon, the Call Post sportswriter who appeared to cover the Women’s Dipsea Hike beat for the newspaper. “Coming in after a seven mile jaunt over the trail, most everyone who came in finished in splendid shape.”

The competitors in the inaugural Women’s Dipsea Hike were so overjoyed with the opportunity to race that 22 of them – including Edith Hickman – personally signed a typed letter of gratitude addressed to James dated May 1, 1918.

“The girls who participated in the Women’s Cross Country Hike, wish to thank you for your good fellowship and ability in arranging the Women’s Cross Country Hike. We all understand the great amount of work connected with a race of this kind.

“You managed the start and finish, also many little comforts during the day for us in a way that could not possibly have been better. We only hope that you will have charge of the same kind of race for us next year. With kindest regards from all of us and thanking you again, we are very truly yours.”

Before the second Women’s Dipsea Hike, the Call Post’s Alma Reed wrote a long story featuring Miss Hickman explaining how she won the race in 1918. She offered “inside tips” to competitors ranging from “don’t underestimate the value of training” to “eat nourishing food … eliminate fruit from your meals at least during the two days before the race as fruit tends to create acid” to footwear of men’s socks and “soft, light, flat heeled shoes, reaching above the ankle and built on the Boy Scout model, are the proper kind.”

Clothing for the race changed, too, becoming lighter, shorter, and more colorful. Miss Hickman opposed riding trousers and shirt waist to “more comfortable, if less attractive looking, bloomers and middy blouse.”

By the third year of the Women’s Dipsea Hike entries soared to 619. Their names were all listed on the sports page of the Call Post. Mrs. Shortall again announced that all entrants would need to submit to “an examination of the heart” to qualify for the race. The exam had to administered by a family physician or three “specialists” who volunteered for the Call Post to examine the entrants to confirm they were fit enough to compete.

Response was so great that a Call Post headline blared “Entries So Numerous For Girls’ Hike That Trail May Be Widened.” Noon, who gave George James the nickname “The Sultan of the Dipsea,” evidently attended the Third Women’s Dipsea Hike and offered an eyewitness account.

“To see them sprinting down the beach at Willow Camp at the finish of the Dipsea hike Sunday, with their faces wreathed in smiles, was a real treat,” Noon wrote. “It also proved that girls have the same do or die spirit that men have when it comes to battling for athletic supremacy.

“With but one or two exceptions, most every girl who competed in Sunday’s classic hike, reached the finihs (si) in tip-top shape. And remember, the distance between Mill Valley and Willow Camp over the Dipsea trail, is exactly seven miles. We’ll wager that a bunch of men would not have finished in any better shape than the girls who hit the trail for Willow Camp last Sunday.”

The San Francisco Bulletin took over sponsorship of the Women’s Dipsea Hike in 1921. Emma Reiman claimed the first of her two victories in the event after placing second the previous two years.

“The remarkable feature of the finish of Miss Reiman was her physical condition. She ran across that line in beautiful form – athletic form, I mean – and had every appearance of having just stepped out of a bandbox. There was not the slightest trace of exhaustion,” wrote William Unmack for the Bulletin. “Men athletes usually come in with their faces streaked with perspiration, drawn lines with signs of distress. Not so Emma Reiman. There was no dust, perspiration-streaked face, no drawn lines or signs of distress.”

For her victory, Miss Reiman received two prizes – a winner’s cup from the Bulletin and a $75 pearl necklace offered by the Oriental Pearl Company. Initially, George James thought it was unfair that Miss Reiman was given two prizes and the prize committee withdrew the pearl necklace. However, after an argument that lasted more than an hour, it was decided to leave the decision to Rutherford M. Rau, head of the Oriental Pearl Company, who donated the necklace. He immediately handed it back to Miss Reiman.

The Women’s Dipsea Hike had evolved into a more revered event than the men’s-only Dipsea Race that the Olympic Club established in 1905. Newspaper photos showed spectators lined up five deep behind ropes. It was estimated that there were 5,000 spectators in attendance.

“The town turned out en masse to see the start of probably the greatest competitive event for women ever held in California,” the Call Post newspaper noted in 1920. “It took the entire forces of Marin County deputies to hold the crowd back and allow the winners ample space to dash madly on their way.”

Unfortunately, the Women’s Dipsea Hike lost steam, though because no fault of its own. There were fans of the race, but also many detractors. The pioneering women’s sporting event ended following the 5th Women’s Race in 1922 when Miss Reiman won in a record time of 1:12.06. By then, local churches and physicians were objecting to the competitors’ fashion (“hiking costumes”) and “undue stress on women’s bodies”, health concerns that the competitors were compromising their reproductive systems.

In truth, the Women’s Dipsea Hike lost its biggest supporter. George James became ill and died. He did not complete the 239-page scrapbook he created, leaving numerous pages blank following clippings of the race in 1921.

In his story in the Olympian following the inaugural Women’s Dipsea Hike 100 years ago, the headline was “Will Woman Athlete Eclipse Man?” James was a visionary for female athletes.

“The Woman’s Cross Country Race over the Dipsea Trail has demonstrated the fact that women are earnestly going in for athletics,” James wrote in April of 1918. “To me the day is not far distant when women will excel men in competition – particularly in tests of endurance.”